In 2009, Eric Fèvre’s team was researching a range of zoonotic diseases—those passed from animals to humans—in western Kenya. The local hospitals reported many cases of the debilitating bacterial illness brucellosis. But when Fèvre’s team—from the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) and the University of Liverpool—used a different method to test people and their livestock, they found only a few had the disease.

"This is weird,” Fèvre thought. “Let’s dig deeper.” When the researchers did, they discovered that the cheap testing method used in hospitals because of its low cost and ready availability—the Febrile Brucella Agglutination Test, or FBAT—was leading to a lot of false positives.

“That matters, because chronic brucellosis is a very unpleasant infection that requires treatment. Patients being misdiagnosed were undergoing six weeks of several heavy antibiotics, potentially leading to issues like drug resistance,” says Fèvre, a jointly-appointed professor of veterinary infectious diseases at the University of Liverpool and principal scientist at ILRI. They also spend money on unnecessary medicine, adds Mathew Mutiiria from the Government of Kenya Zoonotic Disease Unit.

“Treatment takes a long time, and during this period, many people are unable to perform their usual productive work.”

In other parts of Kenya, particularly among pastoralists, brucellosis is widespread—but it’s often invisible. Sick animals frequently abort their first pregnancies but can otherwise appear healthy. And in humans, the disease’s symptoms—chronic fever, joint and muscle pain, fatigue—can be confused with other illnesses, such as the flu or malaria.

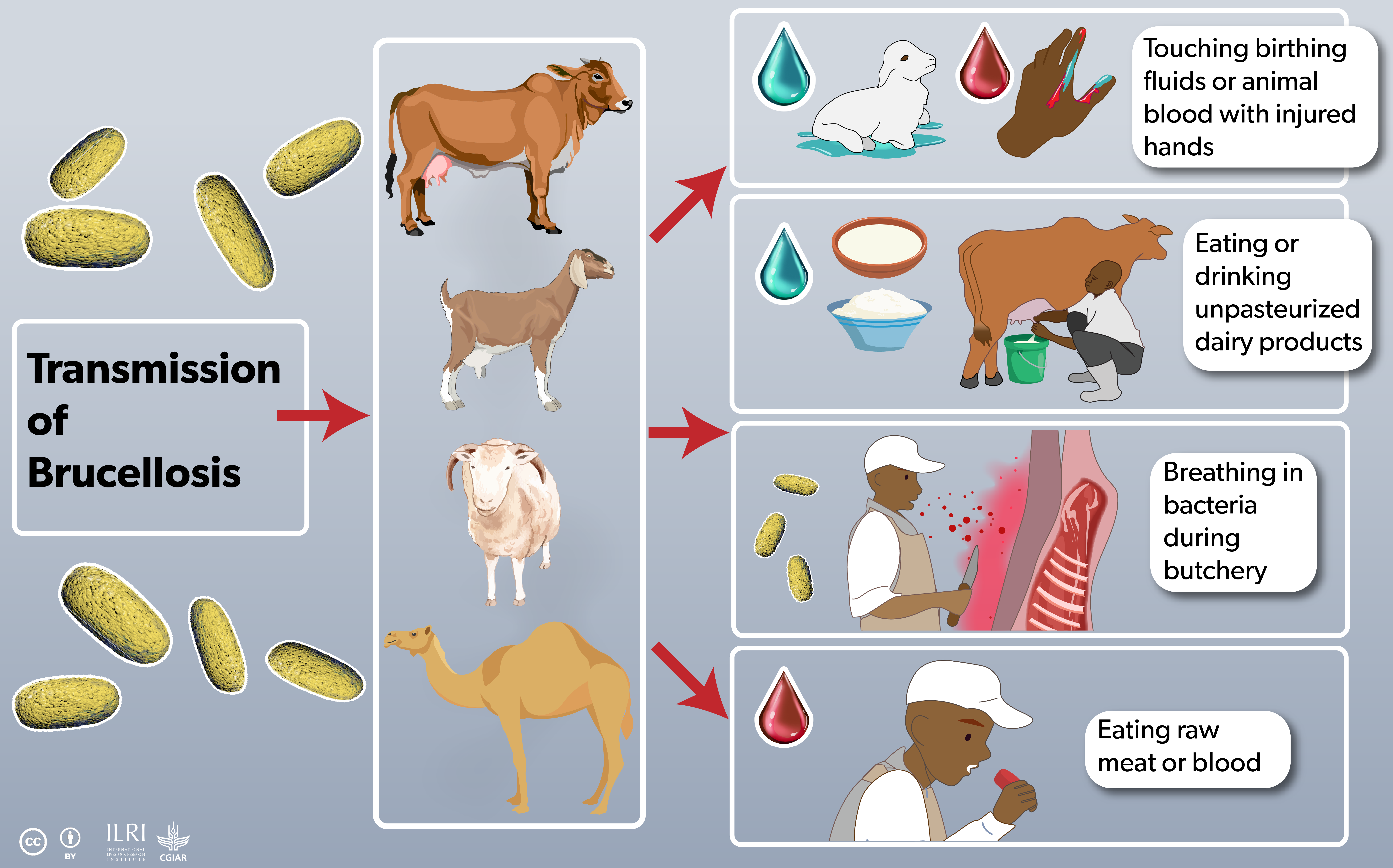

In Northern Kenya, it’s estimated that up to three-quarters of households are infected with the disease, which is transmitted through direct contact with infected animals, carcasses, unpasteurized dairy products, or undercooked meat. A farmer might contract it while delivering a baby goat, a city-dweller through drinking infected milk. The country as a whole records more than 100,000 brucellosis cases per year.

Brucellosis is a zoonotic disease that can be transmitted from animals to humans in a multitude ways. Infographic ILRI/Annabel Slater

Rural and regional hospitals therefore need a reliable method of diagnosing brucellosis. The most accurate tests—enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests—are time consuming and much more expensive than the $US0.20 FBAT ones. “They cost several dollars per test, which is unaffordable for many health units,” says Fèvre.

But there was another test on the market—the Rose Bengal Test (RBT). It was mainly used to test animals, but not routinely for humans. Fèvre and his colleagues got funding from the UK government to test the performance and cost-effectiveness of the RBTs compared with the status-quo FBATs. Over a six-month period, they collected 180 patient serum samples. Testing with FBAT, the hospitals turned up 24 positive results. When the ILRI scientists later had those same samples tested with RBT at the field laboratory, they identified only three brucellosis cases.

“Extrapolation to the national level [in Kenya] suggested that an estimated US$ 338,891 per year is currently spent unnecessarily treating those falsely testing positive by FBAT,” the researchers wrote. At around US$ 0.50 per test, the Rose Bengal Tests cost slightly more—but the study suggested that in the long run, using them would save Kenya thousands of dollars.

Everyone in the room

This research wasn’t happening in isolation, says Fèvre. “It’s about starting with curiosity-driven research, then working in tandem with the key stakeholders to make sure we’re producing what’s needed.” The scientists shared findings early with Mutiiria and his government colleagues at the Ministry of Health and Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock Development, got their support for funding, and involved them throughout the years-long projects.

“This is evidence-based research, helping us give policy direction,” says Mutiiria. “The research resonates with our needs and leads to policy implementation.”

When Kenyan officials sat down to write a National Strategy for the Prevention and Control of Brucellosis in Animals and Humans (2021–2040), they included a recommendation to hospitals to make the switch from FBAT to the new RBT tests (the health system is decentralized in Kenya, meaning each county makes its own decisions about health expenditure.) “But despite us having put this in the strategy, we found that this was not being implemented,” says Mutiiria.

So in September 2024, Mutiiria and Katie Hamilton—also a jointly appointed scientist at ILRI and the University of Liverpool—got everyone into the same room for a big meeting on brucellosis testing. Scientists, policymakers, rural hospital staff, agricultural technicians, and nomadic pastoralists gathered for two days near Nairobi.

“Everyone in the room was aware of the test’s drawbacks, so they were happy to discuss creating a policy,” says Hamilton.

In November 2024, the Kenyan government issued a policy brief, directing all hospitals to use the Rose Bengal Test for brucellosis testing. “The significance is that it provides clear direction,” says Mutiiria. “If this policy brief is adopted, it will reduce the number of people unnecessarily visiting health facilities for treatment of diseases they do not have. Proper diagnosis will reduce the workload on healthcare systems, as only those who are truly sick will be treated.”

At the Kenyan government’s request, Hamilton is currently collecting definitive evidence of the tests’ relative accuracy. She’s liaising with hospitals across Kenya, which are sending serum samples to ILRI’s laboratories. There, Hamilton’s team will run three tests on each sample—the FBAT, the RBT, and the gold standard PCR test.

On the government side, some more work is needed to ensure the accessibility and availability of the test, says Mutiiria. “We all agree it’s a better test, but making it available everywhere might be a challenge.”

Brucellosis reservoirs

While accurate testing is essential for treating brucellosis and avoiding misdiagnosis, reducing the actual burden of the disease requires a One Health approach, says Bernard Bett, a veterinary epidemiologist who leads ILRI’s One Health Centre in Africa (OHRECA).

Health systems alone can’t put much of a dent in this disease—because this is a zoonotic illness, caught from animals, you can’t cure people without first curing their herds. “Treating the patient today isn’t enough—because they go back home, get reinfected by consuming the same milk, and return to the hospital. The cycle continues.”

Bett’s teamhas created a risk map for Kenya, showing the locations most affected by brucellosis—in general, arid and semi-arid pastoral areas. But while the disease’s prevalence can top 40% in some human communities, in those same communities the percentage of sick animals is usually below ten percent.

![Rural and regional hospitals therefore need a reliable method of diagnosing brucellosis. The most accurate tests—enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests—are time consuming and much more expensive than the $US0.20 FBAT ones. “They cost several dollars per test, which is unaffordable for many health units,” says Fèvre. But there was another test on the market—the Rose Bengal Test (RBT). It was mainly used to test animals, but not routinely for humans. Fèvre and his colleagues got funding from the UK government to test the performance and cost-effectiveness of the RBTs compared with the status-quo FBATs. Over a 6-month period, they collected 180 patient serum samples. Testing with FBAT, the hospitals turned up 24 positive results. When the ILRI scientists later had those same samples tested with RBT at the field laboratory, they identified only three brucellosis cases. “Extrapolation to the national level [in Kenya] suggested that an estimated US$338,891 per year is currently spent unnecessarily treating those falsely testing positive by FBAT,” the researchers wrote. At around $US0.50 per test, the Rose Bengal Tests cost slightly more—but the study suggested that in the long run, using them would save Kenya thousands of dollars. Everyone in the room This research wasn’t happening in isolation, says Fèvre. “It’s about starting with curiosity-driven research, then working in tandem with the key stakeholders to make sure we’re producing what’s needed.” The scientists shared findings early with Mutiiria and his government colleagues at the Ministry of Health and Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock Development, got their support for funding, and involved them throughout the years-long projects. “This is evidence-based research, helping us give policy direction,” says Mutiiria. “The research resonates with our needs and leads to policy implementation.” When Kenyan officials sat down to write a National Strategy for the Prevention and Control of Brucellosis in Animals and Humans (2021–2040), they included a recommendation to hospitals to make the switch from FBAT to the new RBT tests (the health system is decentralised in Kenya, meaning each county makes its own decisions about health expenditure.) “But despite us having put this in the strategy, we found that this was not being implemented,” says Mutiiria. So in September 2024, Mutiiria and Katie Hamilton—also a jointly appointed scientist at ILRI and Liverpool—got everyone into the same room for a big meeting on brucellosis testing. Scientists, policy makers, rural hospital staff, agricultural technicians, and nomadic pastoralists gathered for two days near Nairobi. “Everyone in the room was aware of the test’s drawbacks, so they were happy to discuss creating a policy,” says Hamilton. In November, the Kenyan government issued a policy brief, directing all hospitals to use the Rose Bengal Test for brucellosis testing. “The significance is that it provides clear direction,” says Mutiiria. “If this policy brief is adopted, it will reduce the number of people unnecessarily visiting health facilities for treatment of diseases they do not have. Proper diagnosis will reduce the workload on healthcare systems, as only those who are truly sick will be treated.” At the Kenyan government’s request, Hamilton is currently collecting definitive evidence of the tests’ relative accuracy. She’s liaising with hospitals across Kenya, which are sending serum samples to ILRI’s lab. There, Hamilton’s team will run three tests on each sample—the FBAT, the RBT, and the gold standard PCR test. On the government side, some more work is needed to ensure the accessibility and availability of the test, says Mutiiria. “We all agree it’s a better test, but making it available everywhere might be a challenge.” Brucellosis reservoirs While accurate testing is essential for treating brucellosis and avoiding misdiagnosis, reducing the actual burden of the disease requires a One Health approach, says Bernard Bett, an animal and human health scientist who leads ILRI’s One Health Centre in Africa (OHRECA). Health systems alone can’t put much of a dent in this disease—because this is a zoonotic illness, caught from animals, you can’t cure people without first curing their herds. “Treating the patient today isn’t enough—because they go back home, get reinfected by consuming the same milk, and return to the hospital. The cycle continues.” Bett’s team has created a risk map for Kenya, showing the locations most affected by brucellosis—in general, arid and semi-arid pastoral areas. But while the disease’s prevalence can top 40 percent in some human communities, in those same communities the percentage of sick animals is usually below ten percent.](https://www.ilri.org/sites/default/files/inline-images/53306518053_6da30f4dd4_o.jpg)

About 70% of Kenya’s milk is sold in informal markets. Simple food-safety practices such as transporting milk in clean containers and boiling milk on arrival help reduce risks of diseases like brucellosis. Photo ILRI/Kabir Dhanji

That’s because milk is a common source of infection and is often pooled and shared widely within households and among neighbors, Bett says. But it also means that a relatively small number of animals act as brucellosis superspreaders. “It could be one to two or three animals in a herd.”

Identifying and culling those few animals could therefore significantly reduce human infection and the brucellosis burden on the health system, and that is the approach used in European countries—a method that has contributed to eliminating brucellosis there. “But convincing farmers in an African setting is difficult because these animals are often highly valued and loved,” Bett says. “We need screening, surveillance, and highly accurate diagnostic tests to identify infected animals clearly to the farmers.”

Practicing medicine isn’t just the purview of the medic working in the dispensary, he points out—it also encompasses the work of preventing spillover from reservoirs of zoonotic disease.

More work is needed on multiple fronts, Fèvre says—developing an animal vaccine, for instance, and educating urban audiences about the disease. “Consumers don’t think of milk as a brucellosis risk. They see it as a farm problem, not a food safety issue.”

“But progress comes in steps. We’re not constantly making discoveries every second. We take one step forward, then there’s a period of reflection, analysis, and planning. It’s iterative, because government decision-making is inherently conservative.”

The policy directive is a big achievement, he says. In the future, he hopes it will also be picked up by the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention as a regional recommendation.

In the meantime, the directive “means that 50 million Kenyans—Kenya’s entire population—should have access to better diagnostic processes. If someone has brucellosis, it's more likely to be accurately diagnosed. And more importantly, if they don't have it, they won’t be misdiagnosed and wrongly treated,” Fèvre says.

“The primary benefit is better health outcomes for patients with this neglected tropical disease.”

Source: ILRI

Facebook

Facebook  Youtube

Youtube  VN

VN

Youtube

Youtube  Linkedin

Linkedin  Facebook

Facebook